Not much is known about Ernst Erdmannsdörffer, who defended a thesis on the rhymes of the Troubadours in 1895, and published it, with a modified title, in 1897. His only known biography is his work, in Latin, a Vita which takes up less than a page of his Reime der Trobadors of 1895. We find there his date and place of birth, 27 January 1870 in Łuków (Luckau in German), Lower Lusatia, and the names of his parents. Nothing about his life after 1897.

Erdmannsdörffer’s thesis is that the study of rhymes makes it possible to restore the pronunciation of ancient Occitan. The first publication was strongly criticized by Edmund Stengel and by the editorial staff of Romania. The title of the final version becomes Reimwörterbuch (rhyming dictionary). The review of this edition by Oscar Schultz-Gora is less negative. The book is regularly mentioned in even recent bibliographies, which suggests that it wasn’t all that bad.

Click here to read or download Ernst Erdmannsdörfer Die Reime des Trobadors (#125 of the Documents pour l’étude de la langue occitane series) from the IEO Paris website.

in the neighbouring Seine-et-Marne. He spent a part of his student’s life in occitan protestant strongholds (Nerac, Montalban) but he finally passed five exotic language diplomas at the Paris “Langues Orientales” high school, and worked the rest of his life as a french foreign affairs agent. Interested by the Occitan language, he learnt it and soon published translations from Persian and from Ancient Greek. He missed some tools and this is mainly the reason for which he built them: a huge French-Occitan dictionary, and an Occitan grammar.

in the neighbouring Seine-et-Marne. He spent a part of his student’s life in occitan protestant strongholds (Nerac, Montalban) but he finally passed five exotic language diplomas at the Paris “Langues Orientales” high school, and worked the rest of his life as a french foreign affairs agent. Interested by the Occitan language, he learnt it and soon published translations from Persian and from Ancient Greek. He missed some tools and this is mainly the reason for which he built them: a huge French-Occitan dictionary, and an Occitan grammar. Camille Chabaneau, a Nontronh-born postman, managed to get the position of Occitan professor in the University of Montpellier. Twice published as part of reviews, this study on the language and litterature of Limousin managed to be printed separately in 1892, with two appendixes by Alfred Leroux. Paul Meyer, from the Paris-based Romania, did not like Chabaneau was not obeying his theses on the “former language of Oc”. Necrologies by Jean Daniel and Antoine Thomas, detail the extensive coverage of the limousin language and history by Chabaneau and Leroux .

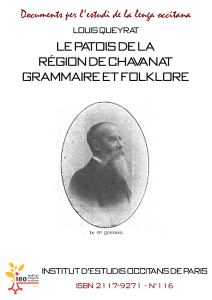

Camille Chabaneau, a Nontronh-born postman, managed to get the position of Occitan professor in the University of Montpellier. Twice published as part of reviews, this study on the language and litterature of Limousin managed to be printed separately in 1892, with two appendixes by Alfred Leroux. Paul Meyer, from the Paris-based Romania, did not like Chabaneau was not obeying his theses on the “former language of Oc”. Necrologies by Jean Daniel and Antoine Thomas, detail the extensive coverage of the limousin language and history by Chabaneau and Leroux . We follow the republication of Doctor Louis Queyrat’s masterpiece with his lexicon of Chavanac language, an Occitan dialect at the boundary of Auvergnat and Limousin.

We follow the republication of Doctor Louis Queyrat’s masterpiece with his lexicon of Chavanac language, an Occitan dialect at the boundary of Auvergnat and Limousin. Queyrat was head of the dermatology service of l’Hôpital Ricord, a venereal hospital in Paris, now Hôpital Cochin.Born in Chavanat, at the boundary of Auvergnat and Limousin dialects, he never stopped to speak his language with the many Creusois that were living in the Paris area. During a great part of his life, he prepared a complete study of his language, and decided to publish it in the 1920s.

Queyrat was head of the dermatology service of l’Hôpital Ricord, a venereal hospital in Paris, now Hôpital Cochin.Born in Chavanat, at the boundary of Auvergnat and Limousin dialects, he never stopped to speak his language with the many Creusois that were living in the Paris area. During a great part of his life, he prepared a complete study of his language, and decided to publish it in the 1920s. He also published many books about the history, the geography, and the language of Occitania.

He also published many books about the history, the geography, and the language of Occitania.

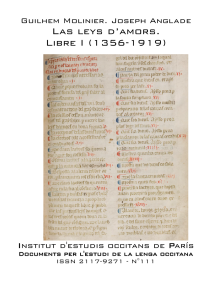

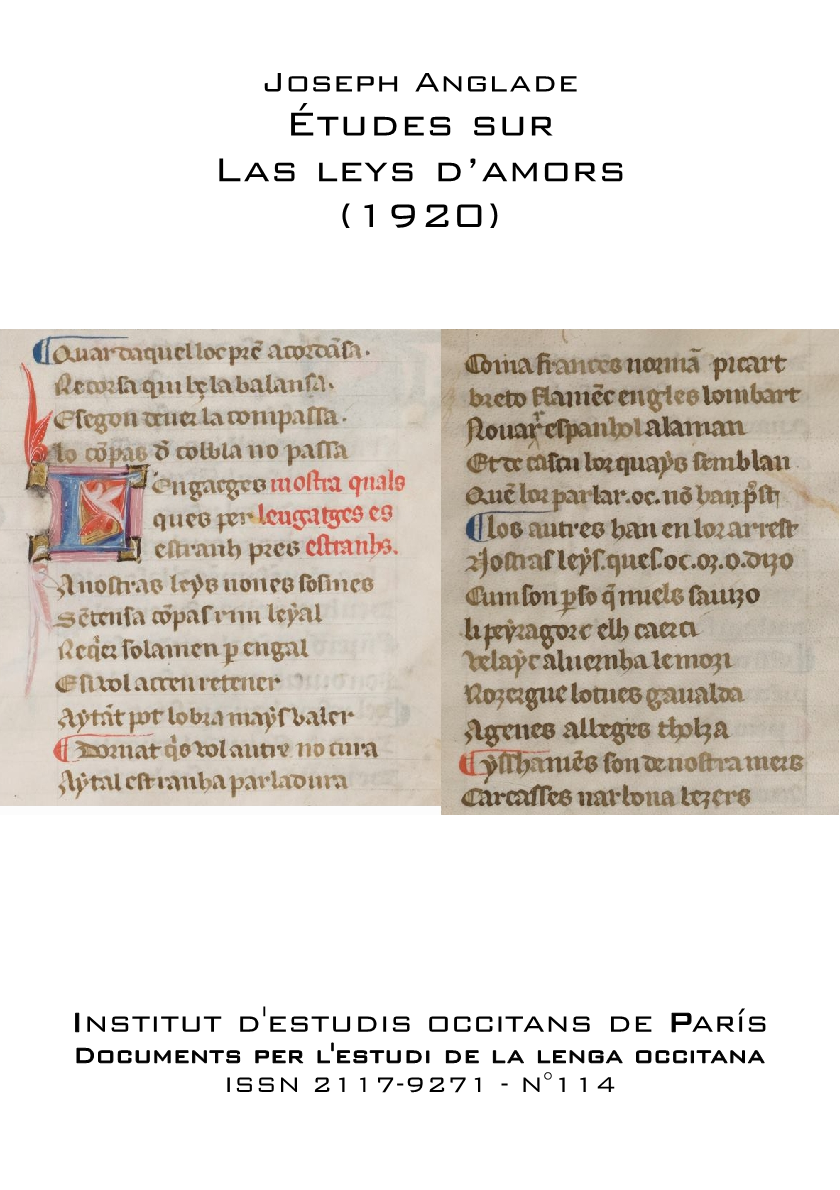

The third volume includes the Book 3 of the Leys d’amors, which is the grammar proper. Click

The third volume includes the Book 3 of the Leys d’amors, which is the grammar proper. Click